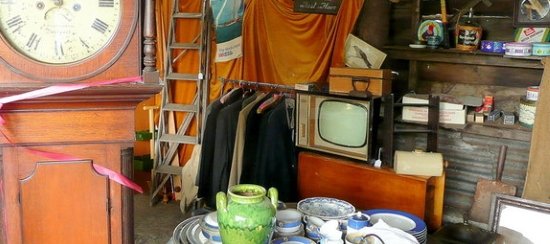

When my sons were little, my idea of an evening on the town was to attend an antiques show or an auction. I usually set a limit on how much I would spend, perhaps the equivalent of dinner and a movie.

In a Tulsa auction house, an Imari bowl came up for sale – black background, colorful chrysanthemums and a green and purple bird inside, black flowers on the outside. I lifted four fingers. The auctioneer tried valiantly to get another bid. I got the bowl for four dollars!

The time when Japanese porcelains were not highly regarded is long past.

That Imari bowl – old, valuable (recently evaluated at $3000), and cherished – began an extensive collection of porcelain and pottery that provides me unending pleasures. Pottery may be the most accessible of all enduring arts. Collectors can still find Japanese and Chinese pots and porcelain plates, and Imari for under $100.

The spectacular rise in popularity and price of Chinoiserie has caused antiques dealers and appraisers to pay closer attention to Asian artifacts, art, furniture, kimonos, and particularly to porcelain. Such “Orientalism” may not be very old, but may be antiques-in-the-making.

One way to start collecting is to choose a category such as bowls, plates, pitchers, teapots, or “tea ceremony” cups, or perhaps all blue or blue-and-white items which show up frequently at flea markets. Also collectible is “brocade Imari,” the Japanese style, a mass of elaborate, brilliant-colored brocade covering the whole surface.

Few ceramics associated with the art of the potter did not originate with Chinese craftsmen. Even with advanced knowledge of techniques and science, modern potters rarely achieve the perfection of the art produced by early potters of the Far East. In Northern China tombs dating back to 2000 B.C., boldly shaped jars have been uncovered. These, made by the “coiling” technique, were decorated with vigorous designs in red and black clay slips on buff-toned burnished earthenware. The slip is clay reduced to a liquid batter, used for making, coating, or decorating pottery.

During the Great Bronze Age of China, artists turned out high-fired stoneware with a “tight fitting” olive-green glaze, inspired by the form and decoration of contemporary bronzes.

During the T’ang dynasty (A.D. 618-906), Chinese artists responded to the trade needs of Central and Western Asia with ceramic tomb wares. These often were yellow-toned and green-toned glazes, now referred to as “egg and spinach.”

Toward the end of the T’ang dynasty, the Chinese potters’ most significant discovery was the method of producing a white, translucent body, a hard-paste porcelain. The artist achieved this by fusing China-clay (kaolin) and China-stone (petuntse) at a temperature around 1300 degrees. Sometimes, gold on a piece added a lustrous beauty.

From the time of the reign of the Ming Emperor Hsuan Te (1426-1435), potters commonly used a “reign-mark” in underglaze blue. Collectors should not assume that this mark indicates a special antiquity, since other potters used it later as a mark of veneration. (Some of this pottery is well-worth acquiring.) Trading with Europe began as early as the 16th century; blue-and-white porcelain was shipped to European countries where the aristocrats went head over heels for Oriental furniture, pottery, and art.

In Japan, by the 16th century, the “Tea Ceremony” (chanoyu) gradually changed from meditation to a cultural and social experience. Some tea masters decreed specific utensils. Ordinary tableware was not aesthetically acceptable. Outstanding ceramists began working to perfect the low-fired earthenware, “Raku.” These hand-molded forms, with soft lacquer-like glazes in black, yellow, or red, proved especially appealing.

In the 16th century, the Japanese warlord, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, launched military excursions against Korea and brought back many Korean prisoners who were potters. Some of these Korean potters, with their families, taught their expertise to the Japanese. One well-known Korean potter, Yi Samp’young, took the Japanese name Kangagae Sambei. In 1616, he found a mine of white porcelain in Japan that led to establishing the most outstanding porcelain in the world. Imari takes its name from a port in Japan, near Arita, where Sambei discovered the porcelain clays. With adaptations from the Chinese, originally Imari evolved as blue-and-white porcelains. The Korean excursions came to be known as the “ceramic wars.”

Early Imari was a white porcelain or a “sometsuke” – blue and white, dating from around 1624 to the 1700s. The Maeda clan started porcelain manufacture in 1656, bringing to perfection in the next 60 years a distinctive enameled porcelain known as Old Kutani.

Four important dates are evident in the history of Imari ware made for export:

First, in 1867, Mizuhoya usa-ur visited the World’s Fair in Paris and brought back overglaze enamel materials and fashioning plaster molds that had been unknown in Japan.

Second, in 1868, the German chemist, Wagner, the father of Japanese ceramic art of the Meiji period, visited Japan, launching innovative ceramic techniques. That year, when Emperor Meiji took over production of Imari, emphasis went to industrialization. Individuality and handcrafts suffered. The workmanship up to 1868 had been more artistic and aesthetic.

However, some fine Imari was still made, such as “Iro-e” – a generic term denoting overglaze enamel, including “aka-e” – red decoration of a mixture of lead enamel and colcothar. Black lines were sometimes drawn with carbon-laded lead enamel or manganese, and covered with a color enamel.

Documents dating to the 17th century reveal the “akea-e machi” (red picture street, or street of enamelers) in Arita had eleven houses of porcelain decorators where artisans were kept busy painting enamel overglaze colors on blue-and-white wares from the kilns.

The third date, 1900, at another World’s Fair in Paris, Japanese porcelains stole the show!

Finally, in 1927, 200 pieces of pottery, porcelain, and ceramic designs were displayed in a fair at Teiten, Japan.

Today, Oriental, American, and European discriminating collectors are willing to pay high prices for beautiful Imari, kimonos, fine furniture, inro, and netsuke. Netsuke (pronounced nets-u-key, with accent on the first syllable and the “u” almost inaudible) is a combination of two Japanese words meaning “root” and “to hang.”

Since true Japanese kimonos have no pockets, the well-dressed Japanese man carried small personal belongings – money, medicine, and tobacco – in a pouch or case tied to the girdle with a string or a cord. There might be an inro (a small black lacquered box containing seals or medicine) and then a netsuke was attached to the end of the string, serving as a button or catch to hold it between the girdle and garment.

Originally, the netsuke were purely functional. But the Japanese love of beauty (called shibui) and the desire to enhance even the most utilitarian object soon made the netsuke something artistic and elegant. Carvers had a wide choice of material: wood, ivory, horn, lacquer, earthenware, metal, or stone. (Some Japanese claim their deftness with small things, may be due to their eating with chopsticks.) Though netsuke is a tiny object (usually one to two inches high), studying them enables collectors to imagine how artists put heart and soul into carving.

A Japanese antiques dealer tells the story of carver Tomokazu, who made animal figures. Leaving home lightly clad as if going to a public bath, unheard of for four days, he had his family and neighbors worried sick. They were happy when he returned and explained he had intended to carve a netsuke of a deer and had gone into the mountains where he watched these animals. Based on his observation, he carved an image of a deer hardly 1.3 inches tall. Stories are told of carvers who spent months creating a single netsuke. One was a charming puppy playing with a drum by Ran-ichi.

On the netsuke, the artists lavish all their skill and workmanship. Most famous is a two-inch realistic bamboo shoot of ivory. When it is opened, minutely carved scenes are revealed from each of 24 stories of filial piety from China!

Outside Japan, until after the WWII, most Oriental art was undervalued and underpriced. Netsuke were accumulated by a few collectors or tourists who bought them as souvenirs from the Orient. Some of these netsuke may sell for hundreds of dollars, some for thousands, and others are priceless.